The path ahead is misty; I am unsure what lies beyond the thick cover of low cloud I’m approaching. We’ve ascended a steep hill strewn with sheep and divided by dry stone walls. I am wet and cold, and all at once hot and itchy with the walking. As summer holidays go, this could be on par with the least summery of them all.

This was to be expected though. Whilst the rest of the UK had a heatwave last weekend, Rahul and I joined some friends at our regular haunt in the Lake District, the wonderfully rustic family home of our friend Rosie. The trip was always going to feel slightly un-summery to us. Not only was the Lakes pretty much the only place in the UK with temperatures below 20 degrees, but it’s also where we’ve spent a couple of recent New Year's and post-Christmases; huddling round the farmhouse Aga, playing fireside card games, drinking and partying.

I’m not complaining: I love Christmas and I hate London in the heat. And we did get some sunny days which allowed for a gorgeous swim in the River Duddon, so it wasn’t a complete washout. But something about the strange melding of the seasons was so welcome to me, doing a bit of winter in the middle of summer; like a clarion call from my favourite season dropped into my least, reminding me that one day soon I won’t be endlessly sniffling and popping antihistamines, that the nights will draw in again and the leaves will fall.

Winter and summer fight a yin yang battle in one of my favourite Shakespeare plays, The Winter’s Tale, the source of the much quoted and still baffling stage direction ‘exit pursued by a bear’. The story is ‘a tale for winter’ because it is ‘sad’: the jealous King Leontes falsely accuses his wife Hermione of infidelity with his best friend. Hermione dies, and Leontes exiles his newborn daughter Perdita. She is raised by shepherds for sixteen years and falls in love with the son of Leontes' friend. When Perdita returns home however, a statue of Hermione comes to life and everyone is reconciled. Not so sad after all.

The Winter’s Tale is literally a play of two halves: what starts as a searing dissection of human psychology, of betrayal and punishment, falls away to a light pastoral romance in Act IV (the sixteen years later part) and concludes with an act of magic theatricality that tests our suspension of disbelief: a statue comes to life, and with it, hope is restored and forgiveness granted. Inherent in the uneven structure of the play is the transition from the harshness of winter to the promise of summer.

In the essay ‘Seasons and Flowers in The Winter’s Tale’, William O Scott explains how in the play ‘the season of inclement weather, winter, corresponds to unhealthy love: Leonte’s jealousy,’ where conversely ‘Perdita is the trembling and uncertain hope of budding spring.’ Different characters are metaphorically represented by different points of the calendar year. ‘With Renaissance seasonal myth’ - the doubling of the seasons and stages of life; spring as youth and winter as old age - ‘Shakespeare shaped the pattern and enhanced the suggestiveness of his play.’ Instead of life pressing on to its definite conclusion, Leonte’s youth is restored through the reappearance of his wife: this ending would have been a complete twist for Shakespeare’s audience.

Ali Smith’s 2020 novel Summer also warps and subverts our expectations of the seasons - the story is set mostly in February of that year just before COVID hits, and the titular summer is obscured, the present political situation in the UK too far gone to be enjoyed or read as a true summer. The summer in Summer in fact comes from multiple memories of summers long gone: there’s Daniel’s summer at a British internment camp in World War 2, and there’s Grace too, who remembers the summer of 1989 in which she played the role of Hermione in a production of… yes, you guessed it; The Winter’s Tale.

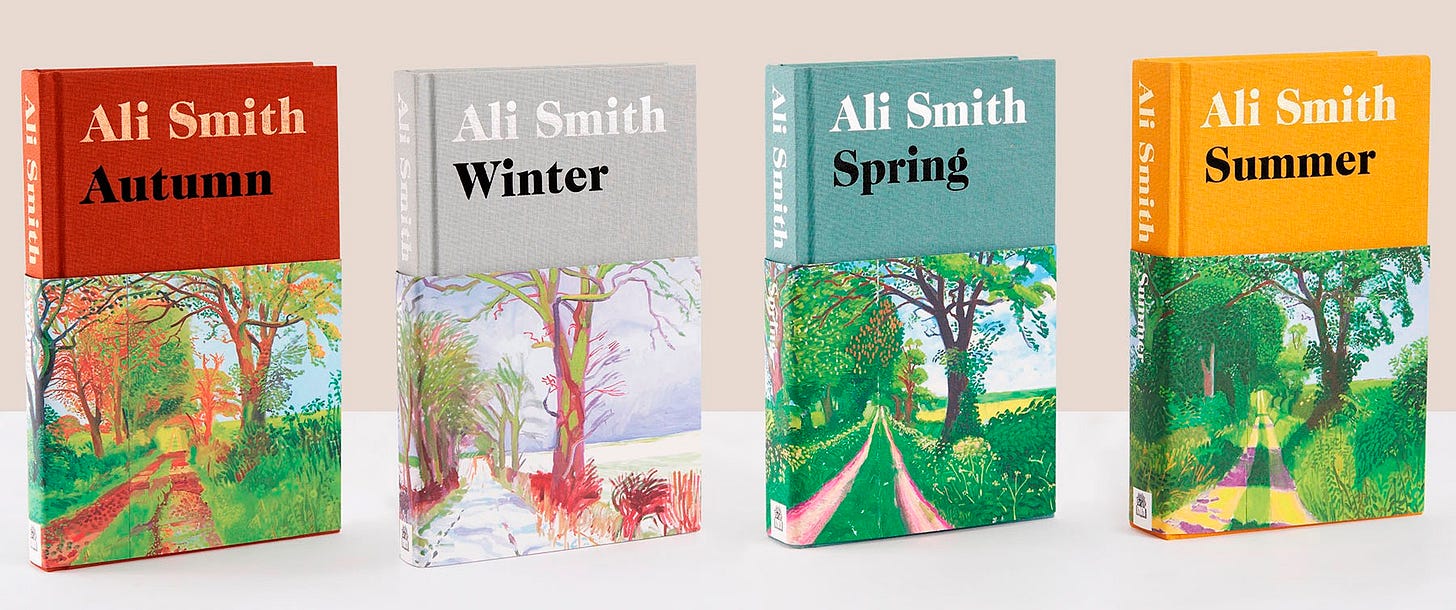

Time is an integral part of Smith’s seasonal quartet. Published at breakneck speed to respond to contemporary Britain as it unfolded, with Autumn coming hot off the heels of Brexit in 2016 and Summer publishing in the middle of the COVID pandemic, these novels very consciously straddle both urgency and timelessness. In her essay ‘Time on our hands in Ali Smith’s Summer’, Dr Flora Sagers writes:

Smith’s mimetic craft combined with the ambient nature of these works, ensures that it is the peculiar sense of the disintegration of boundaries that preoccupies the reader. The distinctions between fiction and reality collapse in the simulacrum of this seasonal quartet, in which past, present, fiction, and reality coexist and coagulate. Time thus appears as both serial and simultaneous. Throughout Smith’s quartet, and most clearly present in Summer, is the idea that time is both, it is ‘now and ancient, time is before and after….if you try to remove your attachment to time, time will….take the skin off you’. Sacha comes to understand this quite literally - her hand is stitched back together after its encounter with the egg-timer - creating a ‘stitch in time’.

for context, an egg-timer is superglued to Sacha’s hand earlier in the story, another of Smith’s playful puns: she literally has time on her hands…

I inhaled Smith’s seasonal quartet as it came out. I went mad with the proximity of the prose; reading about characters nervously taking trains during lockdown, hoping they were wearing their masks properly and not breaking the rules, whilst I was sitting on a train, wearing a mask, doing the exact same thing! The immediacy of it was startling, and the skewered seasons felt reflective of the time we were in that summer in 2020, but there’s more at work in Smith’s books than just relatability.

The characters who discuss The Winter’s Tale in Smith’s Summer say the play is ‘all about summer, really. It’s like it says, don’t worry, another world is possible.’ ‘Shakespeare… infects things with winter precisely so he can have a summer, make a merry tale come out of a sad one.’ In her essay, Sagers says that ‘in writing of the presence of winter in summer through Shakespeare, Smith reminds the reader of the summery nature of this play, the hopefulness of it.’ But she’s doing something deeper. Not only is that same magical, theatrical sleight of hand employed as all the characters from across the quartet return in improbable places, but isn’t central character Daniel’s transition from pensioner in Autumn to a little boy again in his memories in Summer a delightful re-rendering of Hermione’s statue, of Leonte’s redemption?

If Shakespeare and his contemporary audience thought the seasons correlated to a man’s life, then what does mixing them up tell us? That life isn’t quite so simple as mere linear progression. The best years of a life are not always youth: sometimes winter and summers come and go, sometimes unforeseen improbability can change the path of a life in its later stage, as Shakespeare shows.

In the same way, Smith’s quartet looks from the outside like a set of neat, orderly books; each one accepting its place and its title. But by the quartet’s conclusion the book Summer is diluted with winter. This ‘disintegration’ Sagers mentions is apt, so reflective of the chaos of our times. Climate change means we’re getting hotter winters and rainier summers now; as the effects of global warming continue to ravage the planet, soon there won’t be such distinctions as ‘summer’ and ‘winter’. The books are a call to action, evident in the charged choruses that intersperse the chapters, not just a call to idle hopefulness.

For now, maybe a wintery summer is just change happening, cogs calibrating, things working themselves out. I felt that in the Lakes: over the last week some things in my life are settling, shifting, new horizons opening up and uncertainties slowly falling away. How joyous to sit in the eye of the storm, to walk into the rain clouds with my friends, whatever might lie beyond the horizon.

For one of Summer’s epigraphs, Smith quotes Stanley Kubrick from an interview with Playboy magazine. They asked the filmmaker “If life is so purposeless, do you feel that it’s worth living?” He replied: However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light.

‘Exit pursued by a bear’ is Act III, Scene 3, Line 1551, ‘A sad tale’s best for winter’ is Act II, Scene 1, Line 629, ‘Go together, you precious winners all’ is Act V, Scene 3, Lines 3447 & 3448 of The Winter’s Tale by William Shakespeare

I’ve also quoted from ‘Seasons and Flowers in The Winter’s Tale’ by William O. Scott, pg 416-418; ‘Time on our hands in Ali Smith’s Summer’ by Flora Sagers, pg 103-104; as well as Summer by Ali Smith.

The full Stanley Kubrick interview in Playboy, September 1968 is here.